Hola and welcome to your second fun fact of the week,

Today we are going to be looking at orchids.

Orchids are a fabulous and bizarrely diverse group of flowering plants. The name orchid itself comes from the Ancient Green work *** rkhis*** which means testicle, because of the shape of the twin tubers some of them have. In fact they used to be known as bollockwortin Middle English.

They’re actually the second largest group of flowering plants with a current species count of 28,000 and comprise (up to — figures vary) 11% of ALL SEED PLANTS.

Basically there are a FUCK TON of orchids out there. And some of them are super crazy looking.

This one is called the flying duck orchid.

Perhaps the monkey face orchid is more your style?

But I think my all-time favourite has to be the ballerina orchid.

LOOK HOW COOL THEY ARE!

Tune in right to the end there’s a bonus orchid there if you fancy a look. I really hope your testicles don’t look like that though if they do I recommend seeking medical attention.

BUT that’s not what we’re here to talk about. What we are here to talk about is their weird germination habits.

Orchid seeds are TINY. Usually between 0.35mm and 1.5mm long.

This can cause problems for the little orchid seedling because that means there are basically no food reserves for it in there.

That’s one of the great advantages of having a seed — the parent plant packages up some nice snacks (maybe a Fruit Winderand a Frube

- other brands are available *) inside the seed for the seedling to use before it can make any of its own energy. You have to remember that whilst plants are great at making their own food they have to first grow a shoot that can reach the surface and the light. But if you look at that tiny seed there’s basically no food in there to do that with.

How on earth is the little orchid going to grow big enough to reach the surface of the soil, get to the light and start photosynthesising?!

Well it turns out they have some friends (ooh friends).

There’s a handy little funguson hand to help. The orchid allows itself to be infected by the fungus which provides nutrients, mostly in the forms of carbohydrates (mmmm we all need some good carbohydrates).

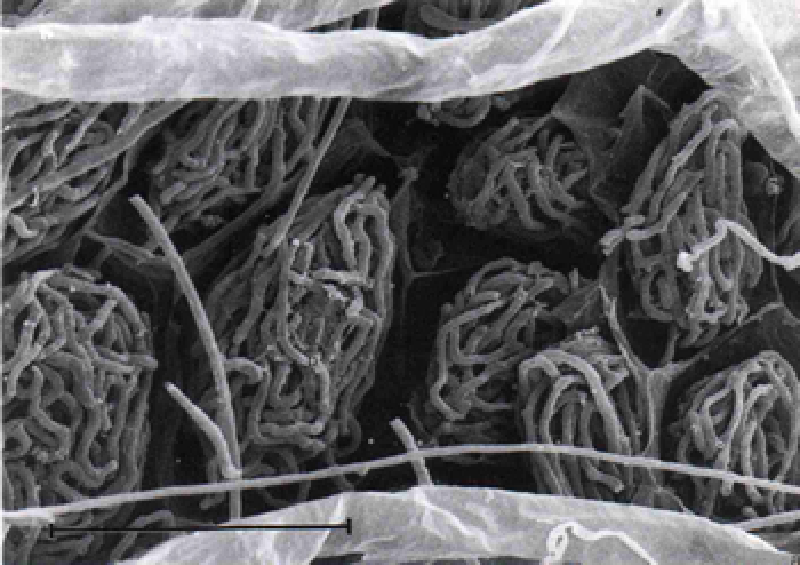

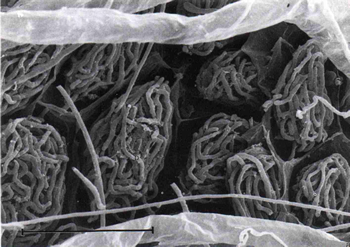

The infection occurs after the embryo takes up water and swells, rupturing the seed coat. The embryo produces a few little root hairs and this is very quickly colonised by the fungus. The fungus then makes special coil structures inside the cells of the orchid which allow for a big surface area for nutrients to be exchanged over. These coils are called pelotons and they look like this:

Sometimes the fungus is the only source of nutrition the orchid receives during its first years of life. In fact some species of orchid don’t photosynthesise at all and solely rely on their fungal friends for food. These orchids can live underground because — hey who needs light to make food when you have a fungus that can do that all for you?

Here’s an underground orchid. Just chillin.

This is an unusual interaction. Usually when plants interact with fungi the plant supplies the fungus with carbon (it has lots because it photosynthesises) in exchange for phosphorous and nitrogen (which plants can struggle to extract from the soil). But here there seems to be a flow of carbon that goes both ways as well as providing phosphorous and nitrogen — so the fungus is doing a lot of the heavy lifting. In fact sometimes (around 400 species) there is no flow of carbon from the plant and all the nutrients are supplied by the fungus.

It’s no wonder then that sometimes the fungi turn against their plants. Occasionally they become parasitic and actually end up killing the orchid. (gasp). But most of the time the orchid is able to keep them in check and they enjoy a long and fruitful and weirdly intertwined life together.

Lots of love to you,

Flora xxx

Here’s the bonus orchid — the white egret orchid

LIVE YOUR LIFE WITH NO EGRETS <3 just egret orchids